Exploring development timing through building a simple trading game

Exploring development timing through building a simple trading game

One of the things I have struggled with in the past is creating accurate estimates for how long projects will take to complete. This is clearly something that expands with experience but by better analysing where I am going wrong, I believe I can steepen my learning curve.

What was the project?

The project on which I chose to explore time estimations was a simple trading game. In the game users start with a little bit of cash; £100 and have the ability to post bids and offers on a single stock. The server would then run a matching algorithm that would match compatible bids and offers and give both users the average of the bid and offer prices. The price at which each trade is carried out is then reported to a graph on the webpage, these are polled.

Where the idea came from

The idea came from a long train of thought which started with a virtual races betting with some friends. I got annoyed because the odds weren't being calculated properly which I didn't realise beforehand and so rather than guarantee a win my strategy halved my starting stake after one race. That led me to think about creating a betting system that people could use with friends, which lead to me thinking about stockmarket game. The first Idea I had was to create a stock market based on payouts from a dice roll. In this version of the idea, each company would represent a strategy. For example, one company might always choose to bet on a 1 coming up. As the underlying outcome is a uniform random distribution over 1-6; no strategy can do better (Within the limits of betting on a single outcome) than betting on 1 every time. Betting on 2 every time is no worse and betting on a number and increasing (modulo 6) that number every time. What is interesting, however, is that, as with the real stock market, different strategies which in the limit tend to the same payoff perform differently. That can lead to differences in the availability of capital. The result of these changes in capital availability is that if a string of 1s comes out of the dice the "always bet on 1" company will not only win each turn but win more each turn.

If a company lost all its money then it would go bankrupt. Players could start a new company with seed capital, they could then define a list of numbers which repeated the company would follow. They could then sell their shares in their company to other players.

I think there are a lot of interesting game-theoretic elements that could be explored in such a game.

An exploration of the timings

In starting to explore the idea I started by defining what objects would be manipulated by the program and the structure that those objects would have.

Company

- Strategy - This defines which of the numbers 1-6 the company will bet on at any time.

- Wealth - This is the cash holdings of the company.

- Shares - These are the units of ownership of the company, owned by shareholders which are another object as defined below.

Shareholders

- Shares - These are declarations of the shareholder's ownership in the companies which this shareholder owns.

- Cash - The cash holdings of this shareholder

I then also considered events that would be possible:

- Buying shares

- Selling shares

- Voting on a change of strategy

- Voting on closing the company and releasing the company's cash to the shareholders.

- Other votes on the actions of the company

It was at this point that I realised this was overly complicated and if I was to build something of this nature it was going to have to be simplified. The simplification I came up with was that there would be only 1 company, the shareholders could buy shares in this one company. There would be no dice rolls and therefore no strategy held by the company. The game would simply be to buy and sell shares in this company. To make this overly simplified game more gamelike, there would be a leaderboard for who had the largest cash holding. Every player would only start with £100. There would be an initial IPO of the company whereby everyone could buy shares for the value defined by the IPO until a set number had been sold.

Those holdings could then be trades between the players by the players posting bids, saying an amount they would pay to receive shares, and offers, saying an amount they would part with their holdings for. These bids and offers could then be matched any time the bid was more than the offer.

Since every player starts with a non-zero amount of capital, this translates to in effect quantitative easing. With every new player, the money supply expands by £100. That will, as all economists know, lead to inflation. In this game, the only asset which can inflate in its price is the stocks of the single company being traded. Therefore over time, the price of the stock will increase. That isn't to say the stock will flow upwards, I expect there to be fractal structures that emerge as the traders believe the stock will rise more than the expansion in the money supply suggest and others will profit from this speculation while others will lose out when there is a price correction.

|

| The initial conception |

First half hour

My plan was to keep the app as simple as possible so if I didn't need to build out database schemes then that was all the better. Clearly, I needed there to be some kind of persistence between requests to the flask app and so I went with Memcached. A tool which I have been wanting to work with in the past but never had a good enough reason to use. It seemed perfect for this use case and after half an hour, which mainly involved searching and experimenting with different python bindings to get Memcached connected to a simple flask app, I had a webpage containing a single list with a number in it that would increment every time the page was loaded. An in-memory hit counter I guess.

Through the next 10 minutes, I was working on defining what I would need to store on the user objects and came up with a simple JSON object that would hold the users.

- Holding

- Cash

- Bid

- Price

- Quantity

- Offer

- Price

- Quantity

Also within that 10 minutes, I made the decision to try to use javascript to render the line chart of prices. My original idea had been to use matplotlib which I have a little experience with and that I had used in a web app to display graphs many years ago for my A level project.

After 40 minutes

At the end of 40 minutes, I had a working line graph. Working in the sense that it was being delivered by the same flask app that I had used to deliver the hit counter I mentioned earlier. The line graph itself had come from a line demo[1].

A scrolling graph

After just 54 minutes into this project, I had a scrolling line graph albeit with random numbers from a list. This didn't even get random values from the server.

2x 35 minutes

After just over an hour I had a form in which the orders could be posted to the server. At this point my mind felt like it needed a rest or at least the nature of the project made this a good stopping point if I needed one. To get through this I reviewed where I was and what tasks I needed to do next:

- Delivering the JS through the flask app (I had just been loading the page with all the JS in a script tag)

- Plan how bid and offer submissions will be updated

- A model for the users holding <- Server side, the client-side had an implementation already

At this point, I considered if it would be worth using WebSockets to deliver the price information. I decided against it as I was just trying to get something working and from previous experience, the WebSockets are a challenge.

Here I sketched out what I was to build for the update endpoint which would be polled by the client.

POST ["user_id"] /update

- Price data []*20 <- as in the last 20 prices

- User data: This would be updated if one of the user's orders had been matched.

Hour and a half

Looking back through these notes and knowing that I spend 10 hours on the project it really shows how the cost to write another line of code is proportional to the total number already written. At this point I had to move the code across to another machine. This set me back about 10 minets as I needed to install Memcache etc and validate that I could get everything working again. It is at this point I decided to write an integration test over the update endpoint to validate it was working how I wanted it to.

The three-hour mark

After three hours I had the update endpoint working with a loop in the javascript polling it once per second. This was being pushed to the line chart so had the server had a meaningful stream of prices they would be displayed on the line chart.

The ToDo list at this point contained:

- Updated the user's information in the UI including their shareholding and their free cash.

- UI bid posting: giving the user the ability to update their offers

3 hours 20

Functionally no further yet we were now in a position to know exactly what we needed to add and add it. The bid and offer form values could be loaded into the javascript model. There was now a submit button on the form that invoked their update. Standing issues:

- We only send 1 as the user_id: There was no way to have more than the 1 user.

- The submission of the orders to the server

- Order matching

The problem of updating the UI

One of the problems I had with updating the form was not so technical as it was semantic. If the user submitted for example that they were prepared to buy 10 shares at £10 that order would be sent to the server. If they then submitted that they were prepared to buy 10 shares at £11 I wanted the server to understand this as an overwrite on the previous order. If their order of 10 shares for £11 is only partially successful, say only 5 of the shares got matched, I wanted the UI to update their live position so as to represent that items have sold. The system shouldn't then resubmit their original order over the top, otherwise with would basically mean that an order for 1 share was an instruction to buy indefinitely. If the UI updated while the user was trying to enter a new order that would be mighty frustrating, so I couldn't implement it that way either.

After all this consideration I decided to go for a system where the user would be able to submit orders through the form but would have their orders updated and displayed separately under the order form. To some people that reasoning would have seemed simple from the off but I liked the idea of keeping it tidy and in one place.

Bid submission working

After four and a half hours (spread over two days) I had the bid submission working. That is to say that user 1 could submit a bid to the server and it would store that bid in its entry in Memcached for user 1. The ToDo list at the time looked as such:

- Order matching

- Multiple users

- Leaderboard

At this point, I was questioning if I should have broken the project down into smaller steps rather than break it down as I go.

Five hours in

Just after five hours into this project (now on a fourth day) I am looking into how I might go about matching the orders. Each user could potentially have a bid and an offer and so for each I generate a stack.

The way I plan to arrange the matching is that there will be two stacks, one of bids and one of offers. These stacks will be ordered highest first and lowest first respectively. The price that the shares will change hands will then be a linear interpolation between the two. This means that neither party has to pay a spread. It also means that the highest bid and lowest offer have priority leading to potentially fewer orders being matched than could otherwise have been possible.

First commit for the order matching code

|

| The order matching method I had in my head |

After six and a half hours I stage the first commit containing the order matching code that was planed above. Looking back over the project now I think this is a particularly interesting time to analyse as the work is a single ticket of an hour and a half. Based on the work so far this is by far the biggest single ticket item. After an hour and a half, it still isn't finished. So what is going on here, can we retrospectively break this task up and then look to see if we could have broken it up apriori.

- The commit it made to a single module file (with accompanying test file)

- 2 implemented classes User and Order - Order also has two child classes which at this point are passed (Bid, Offer)

- The user class has the ability to load itself from JSON and has its own test to validate as such, this could have perhaps been a task in its own right. The only question I would put on that is if it could have been known that the user class would benefit from having the ability to be loaded from JSON so early on?

- The Order is currently just a data class

The only real functionality at this stage is the ability to validate that a trade (as made up of a bid and an offer) can be carried out. The checks are done to make sure the bidder has sufficient funds and the offerer has a sufficient holding. The basics of the trade mechanics are here too in terms of a payment going from the bidder to the offerer and the shares going from the offerer to the bidder.

Almost half the commit of the module is for code that deals with extracting the information from the Memcached database. This was something that should have been known to be a task apriori but I would question given the early stages and the style of this project if having tried to break it out before this commit as a separate project would have been wise. I say this because the structure of the database had not as-of-yet been decided and this was in a way intentional and one of the reasons for using Memcached over a SQL design.

I could perhaps have used the adapter pattern to build the adapter I needed taking from this abstract adapter what the trade matching code would need. Would this have allowed for the project to be better planned? I would argue that to a certain level of abstraction that is what I did yet the adapter wasn't a professional one. The code in this commit around extracting information from the Memcached instance doesn't actually work, yet it doesn't take much for it to work. It, therefore, acts as our adapter would in so much as to allow us to query any information we require without having to have already decided how to structure the database.

If this was a larger project and other developers were working around the same code it would make sense to perhaps formalise the adapter pattern here so that there was more consistency but I maintain my position that the functions to extract the information from Memcached acted sufficiently as an adapter pattern for any project at this stage.

One source of tech dept that I have withdrawn from is not wrapping the Memcached interface up inside my own interface. I would have this as high priority going forward on the project as confusion on the structure and type of what is pushed and pulled from the database would be very easy to make. I made some in the small amount of code that I wrote while exploring this project.

Going back to the question of if this 1:30 commit could have been broken into smaller pieces for more accurate planning. I think if it could have been the place where it could have been around separating the withdrawing from the database from the other functionality.

Building out the matching

Over the next hour, I break out the matching code from the code that deals with extracting the information from the database. I move the classes to their own files to help readability and keep the files concise. These models then get their own tests. I also build out the stacks that contain the orders (Bid, Offer).

The seventh hour

Over the seventh hour, I go back on some of the design decisions from the previous hour.

- TradeMatcher no longer a class as the only data that was being persisted was the two stacks.

- Un-nest the structure of bids and offers in the user object.

I also implement functions for making a BidStack or OfferStack from a list of users. (Each user can have at most a bid and an offer)

Feeling lost again

At the eight hour mark, I start feeling a little lost in direction. I feel that for the trade matching I need a clearer definition of done. I don't know if this is because I should have built more of the testing upfront rather than alongside. Most of the modules are pretty well covered by testing. Over the next ten minutes, I stitched together the final pieces to extract information from the database so I can run an integration test. The test passes.

Multiple users

Although at this stage we have the trade matching and the ability to receive a stream of prices from the UI we are still hardcoded to only use the user with user_id 1. With the nature of the game, there is an importance in encouraging people to not have more than one account. Otherwise, they could easily use their starting capital to bid up the price of the stock. To lower the ease with which this can be done I decided to create a simple email/password login system. I also noted at this point that the simplest thing to implement would be a textbox atop the page where you entered your user id. The javascript would then use that. A good tool for debugging but not for the actual game.

Users would require sessions and what seemed like a lot of extra code. I did feel that such a common use-case for flask would have some online demos of how to produce a similar thing. I ended up finding a really good one[2]. It does make use of SQLite, I had wanted to avoid SQL, but since the only use of the database was for a user table and the definition of the user table already existed it was the simplest path to getting user accounts in my app.

The first thing I tried was cloning the GitHub repo which was referred to by the tutorial and try to get the code running from there. I had a lot of issues with relative references and the app being defined in the __init__.py file.

Once I "fixed" (made work on my machine) the imports I could copy and paste the code across and try to integrate it with my existing flask app. Getting the demo working took half an hour! Perhaps that is slow on my part but the way I approached it was a; run -> fix what breaks loop, until it was working. I don't know before I run the code what the errors will be. One could make the argument that I should check the code for other potential occurrences of the last issue before running again. I would counter that with the fact that in scenarios such as this where it is so quick to just run, it's faster, on the whole, to just run and then fix rather than search. There are systems where "just run" is a bit of a joke because running the system after a change is more involved. It isn't a slow task to spin up a flask instance with python app.py.

Finished?

After 9 and a half hours I have the trading app "working" with a login and sign up page. The styling from the user page doesn't go well with my original trading page.

The app is still without a leader board and I imagine has a lot of issues left to be ironed out with regards to thread-safety.

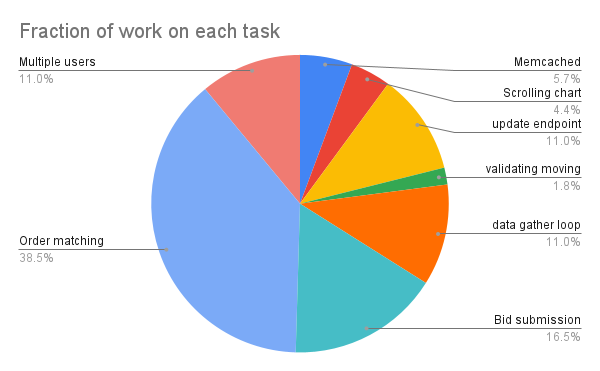

What I really wanted from the project though was the following data about how long it took to get to each stage.

Surprises in how long it took

- Memcached

- Scrolling chart

- Multiple users

- data gather loop

- update endpoint

- Bid submission

- Order matching

- validating moving machine

So how does that compare?

- Order matching

Bid submission

Multiple users

- data gather loop }- Tied; all at about an hour

update endpoint

Memcached

Scrolling chart

- Validating moving machine

I was pretty far off. So why did I think that the longest tasks would be the shortest and the shortest the longest? For me, I have historically found tasks involving integrating another mechanism outside of the core language challenging and time-consuming. I think that in reality the times I have found these tools impossible to integrate weighs heavily on my prediction that they will take a long time. Having seen the results of this little experiment it might be time I attributed less time to a task just because it isn't in the language (And I haven't used it before) and pay more attention to the other elements which are required.

The reason I believed that the order matching code would take so little time is because I believed, I knew exactly what the algorithm was in my head. I think that in that reasoning all objects start in their ideal form. When things are in their idea form interacting with them is simplicity itself.

- Just because it is an external component that needs to be included doesn't mean it will take forever

- Data needs to be transformed into the ideal form for the algorithm and this has a large cost

- Knowing the algorithm doesn't mean you have considered the edge cases. 20% of the cases will take 80% of the work.

Comments

Post a Comment