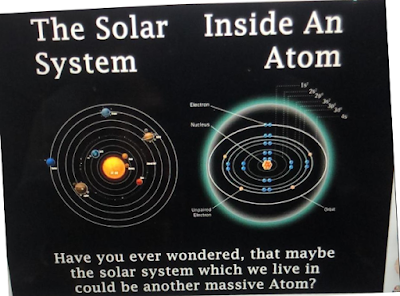

Solar atoms

I recently got a request from a friend to write a post on why this is obviously silly.

I’m actually not sure why it is that silly.

So if you take two diagrams both showing circles orbiting circles and you are told that one is the thing that contains us and the other is the thing that makes us, it isn’t too hard a stretch of the imagination to point at a circle in one image and ask if there is an analogous circle in the other image.

I believe this skill of analogy is one of the things that facilitates human ingenuity.

For, by analogy, you could then think; if one and another is alike perhaps the pattern continues. After all what are those circles in the diagram of an atom made of? Could they too be made of smaller things?

This is similar to looking at the map of the world and asking “Did those two

ever fit together?”

It’s worth mentioning here a favourite quote of mine: (One of my fav quotes)

“All models are wrong but some are useful”

In the two models shown in this Facebook post, this quote applies very well.

In both models, the scales are off. The planets in the solar system are not equidistant from each other and each is so much smaller than the distance between them that each appears only as a point in the sky.

Pale blue dot

If you were to take the perspective of above the solar system to attempt to take a picture hoping to get something like the first diagram you would have to be so far away you would struggle to see any planets at all.

One of the things which is intentionally left out of learning science at school is why we use the models.

Why do we think that the earth goes around the sun at all?

Why do we think atoms exist? Why do we think they are structured like a solar system?

I think the best way to explain this is from the principle of explaining what we see.

Why do these stars move differently?

We have lots of evidence for the heliocentric model but I think the best way to explain the model of the solar system is from the motion of objects we observe in the night sky.

When we look up what do we see?

- The sun as a glowing ball which moves across the sky each day

- The moon which moves across the sky and changes shape in a repeating pattern

- The stars which can only be seen when then sun has set and which move across the sky through the night and change throughout the year, repeating each year.

- Strange stars which follow the following pattern, these are some of the brightest stars in the sky and follow the following strange pattern across the sky.

This is what we can see with our own eyes and as such can note down the patterns over time.

The question is then; what model of reality explains these phenomenon best?

It’s very easy with the benefit of modernity to exclaim the heliocentric model. With the earth a rotating sphere, the “Stars” which move strangely, are actually planets also orbiting the sun. The other stars are far off suns unchanging on human timescales.

For a start we don’t know if there is one sun or many, it always looks the same but would a model of 365 different suns, or indeed more, traveling over the surface of the land all with different longitudes make more sense. Why else would you get seasons?

Out of all the objects that can be seen in the sky why should the sun be the one in the middle? Could the middle not also be the moon?

It turns out geocentrism isn’t as easy to argue against as you might think. That's not to say I suggest you throw out your heliocentric beliefs but it is worth recognising that what we believe about the universe is only one of many possible models and that even ours has its flaws. The best example of this is the speed of stars at the edge of galaxies.

The main point is that the simplest model of the solar system which explains all these observed properties as well as observations of comets and meteors is a heliocentric model based around newtonian mechanics. (The precession of mercury notwithstanding).

|

| Above is a geocentric model which explains the movement of the planets. |

What happens if you cut that half of the half in half?

For as long as humanity has been about to think, people have thought about what things are made of and if there is a limit to how many times you can break things in half. People might argue the smallest this is literally the indivisible, or atom in Greek.

Although the name atom has stuck we now know them to not be indivisible. The standard model of particle physics now describes the atom as a collection of neutrons and protons, themselves made of quarks as well as the electrons which contribute to the chemistry of those atoms.

The experiments which lead us to understand the model of the atom are far less direct than the observations of the motion of objects in the heavens. The experiments on matter are, however, more repeatable in that you have to wait for a celestial occurrence to recur to test your hypothesis whereas you can induce the arrangements of matter.

Some of the experiments are more involved, others are in fact illegal. The question remains the same, what is the best model that can be conceived to match all the data?

I suggest that the model presented by the consensus of modern science is unlikely to be toppled radically. Yes large changes arise, such as Einstein showing places where Newton's laws don’t hold. It was however, more of a refinement than a complete toppling. It leads to a deeper understanding of reality insofar as it applies in a wider range of circumstances and provides an explanation to some questions left unanswered by Newton's model.

A further model will eventually provide a deeper understanding still, perhaps some form of modified gravity that better explains the velocity of stars towards the edge of galaxies.

The experiments required to probe matter at the deepest levels are as a result of this indirect nature far more involved. This has the effect of making them more recent in their development.

Some experiments worth noting that lead us to Bore’s atom (The model shown in the original facebook post):

- Gold foil experiment

- Any chemistry where expelled gasses are taken into account will lead to evidence for both Law of definite proportions and conservation of mass(Up to relatavistic constraints, whereby a consovation of total energy will still be observed)

Bore's atom seems to fit these well what is the issue? The following show the leaky cracks in the Bore model which break to become a torrant. The plumbing of atomics can only be fixed with the more complicated modern view of the world.

- Photon emition from an acclerating charge

- The double slit experiment

- Photoelectric effect

- If the electrons are moving only bound by Coulomb's law then why does spectroscopy always observe the minimum energy needed to liberate the electrons (ionize the atoms) to be quantised (in that they arn't accumulative) and be the numbers that they are.

Getting to our understanding of the atom has been a long journey. For one it really isn’t that obvious that elements should be a set as represented in the periodic table.

I don’t think it is that clear to anyone how you get from:

to :

People have written many books on the story of how the table was derived and how the idea that this set is the most basic set and that gold can’t be made by mixing water and copper in just the right ratio.

Crash course chemistry does a good job of covering the history, I haven't seen a resource that would show from “what is in front of you” that this is the best model. I’m not sure that the number of experiments required could indeed be done in any one person's lifetime.

So could electrons be planets that harbour life?

What we know.

Modern science is based on the rules remaining the same across particular scenes. For example you might question a model of reality whose rules change over time. I would certainly be cynical about a law of physics that applies only on Sundays.

You might also be cynical about laws of physics that only apply in one place and not another. I would certainly be cynical of a law of physics which only applied in countries ending in stan.

All the laws of physics are based on creating a set of rules which don’t vary when you vary something else. These are sometimes referred to and invariances or symitries. The laws of physics are for example rotationally symmetric. You wouldn’t expect the laws to be different based on left and right.

From this, one of the invariances which emerges is that of energy conservation.

If electrons are quanta of energy which obey particular rules to what extent can we talk about them being things at all. We certainly can’t talk about them being here or there and that seems to be a fundamental limit of reality not a technical limit of our apparatus.

Electrons certainly aren't like planets, their orbits are well defined yet their position is very much not. The nucleus of the atom doesn’t emit radiation to the extent required to create complexity in anything orbiting them. Electrons must have only a very specific amount of energy within very specific bounds.

Beyond what is measurable there could be something thinking inside them, to the extent that outside the observational anything uncontraditionary is possible.

There may be a monster under your bed, there might be one in front of you that you just can’t recognise. If it doesn’t help you to better model the world around you in a way that makes your life better then maybe leave it for the fiction section.

But as with the ending of Life of Pi:

Comments

Post a Comment